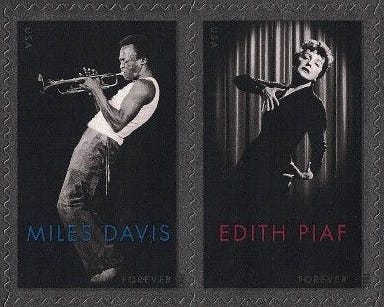

Miles Davis/Édith Piaf

Joint Issue USA/France (2012)

In 2012, the USA and France produced a joint issue honoring a musical icon from each country. What may, at first glance, seem a random and disparate pairing of two subjects on this pane of stamps, becomes clear, once you understand the impact each had on the other’s country, and vice versa.

Édith Piaf

Born Édith Giovanna Gassion, in 1915, she was given the nickname, and stage name, La Môme Piaf, the Little Sparrow, by the nightclub owner Louis Leplée, who discovered her, in 1935. At a petite 4 feet 8 inches tall, the name was certainly fitting. When Leplée was murdered by the mob, in 1936, Piaf teamed up with song lyricist Raymond Asso, who had her change her stage name to Édith Piaf.

By 1940, Piaf was writing many of her own song lyrics – songs that reflected on her own life growing up in the streets. Her popularity grew rapidly, and, after the war, she embarked on an international tour across Europe, the United States, and South America. She met, at first, with tepid success in America, as audiences knew cabaret performers to be gaudy, decadent, and risqué. Yet here was this dour-faced, black-clad performer singing melancholy songs about life’s travails. After one 1947 performance in New York, though, which drew a rave review from the influential critic, Virgil Thomson, her fortunes in America turned. In that same year, 1947, Columbia released Piaf’s first record in America, a song she had written two years earlier, called La Vie en Rose.

The song was a big hit, and would go on to become her signature song. From there, her popularity soared in America, leading to several appearances with Ed Sullivan (the star-maker of that era), and concerts at Carnegie Hall.

Piaf’s songs have been covered by many artists, from Bing Crosby to Grace Jones, and she has been cited as an influence on such artists as David Bowie, Linda Ronstadt, and Elton John, who wrote the dedicatory song, “Cage the Songbird.” In 1998, La Vie en Rose was awarded the Grammy Hall of Fame Award.

Miles Davis

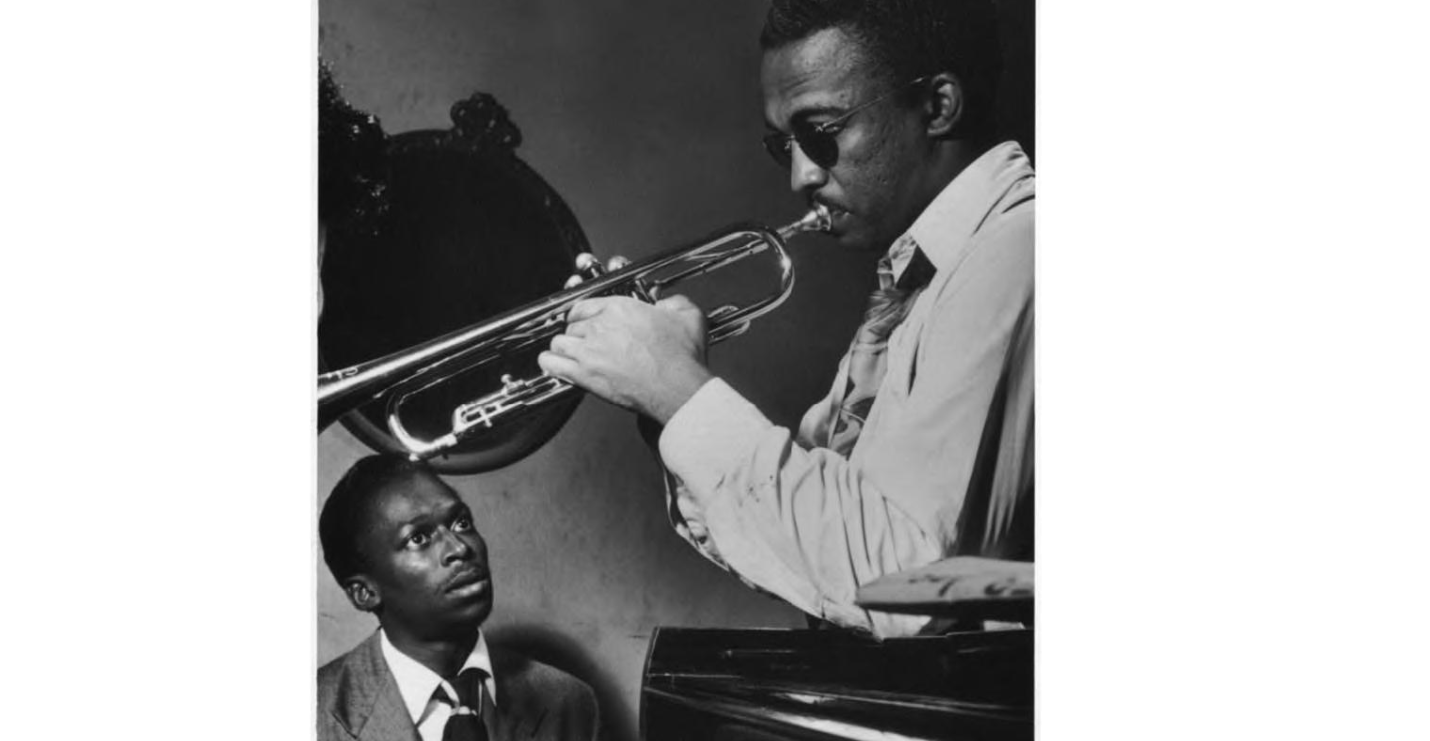

Even the most casual observer of the American music scene will probably know the name Miles Davis (born Miles Dewey Davis III, in 1926), possibly the greatest and most influential jazz artist America has produced. He was born into an affluent family – his father was a dental surgeon; his mother a music teacher – and, in 1944, earned a scholarship to the famed Julliard School. However, he dropped out in 1945 to join sax player Charlie Parker’s quintet, with whom he played through 1948, when he left because of pay disputes.

In January of 1949, he signed a contract with Capital Records, and his nonet (a group consisting of 9 players, including French horn and tuba) recorded 12 songs which, though highly influential with the burgeoning West Coast jazz scene, were, nonetheless, poor sellers. These songs were later compiled into the 1957 album, “Birth of the Cool.”

In that same year, Davis made his first trip to France, to play in the Paris International Jazz Festival. Now, European listeners have, it seems, always held a greater appreciation for jazz than have American audiences. And the French, especially, accepted Davis’s music as no others did. It was love at first sight, for Davis, and the feeling was mutual. The Guardian newspaper, in 2009, quoting film director Rolf de Heer, wrote, “The French were in love with Miles, and treated him like a god. He liked that because it was a form of respect he didn't get in his own country.”

His reception by the French had a profound affect on Davis. Back home in America, he was treated as a lower-class person, with segregation and discrimination still rampant. Paris, continues the Guardian, quoting from Davis’s autobiography, ". . . changed the way I looked at things forever ... I loved being in Paris and loved the way I was treated. Paris was where I understood that all white people were not the same; that some weren't prejudiced."

The Stamps

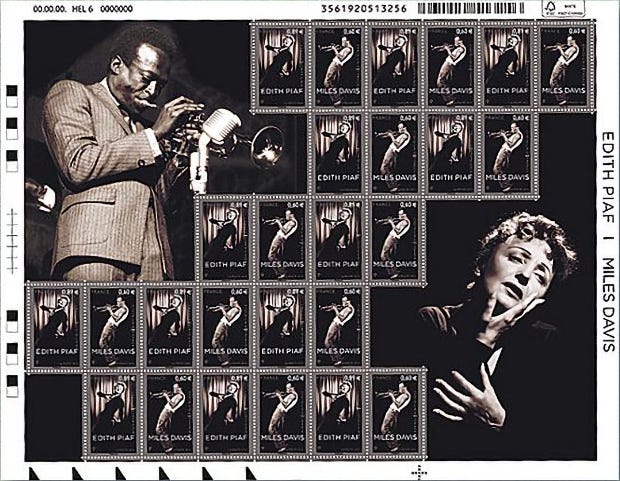

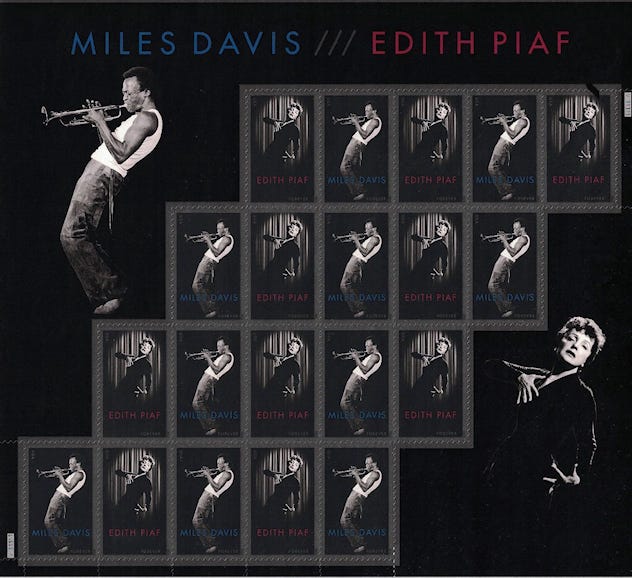

It is no wonder, then, that when the USA and France agreed to a joint issue to celebrate their music culture, these two artists should be chosen as the subjects. The issues were released simultaneously, on June 12, 2012, with virtually identical designs, the only difference (besides country names and denominations, of course) being the white text used for the names on the French stamps, versus the muted color text, on the US versions.

The issue was printed in photogravure, and features both performers in iconic poses. The French issue was produced as a pane of 26, in the selvage of which are images of the two performers in different poses from those on the stamps.

The US issue, on the other hand, was produced in panes of 20, with the stamp images repeated in the selvage. It is the design and layout of the pane which has helped make this my favorite modern American issue. From the similar curved postures of the subjects, to the layout of the stair-stepped stamps mimicking that posture, to the selvage Miles perched on the edge of the stamp step, to the moody black and white photography beautifully rendered in the photogravure process, this pane checks off all the squares to make it a modern classic.