Postage stamps have frequently been used as a means for countries not simply to collect revenue for postal services, but as a medium for making political statements. Thus, the issuing of postage stamps by newly independent countries, or the overprinting of a nation’s stamps by a hostile occupying country, is one of the first orders of business. Another type of political statement for which postage stamps have been utilized can occur when a country declaims their rights to a disputed territory or a border. Such was the case in 1937, with a set of stamps issued by Nicaragua.

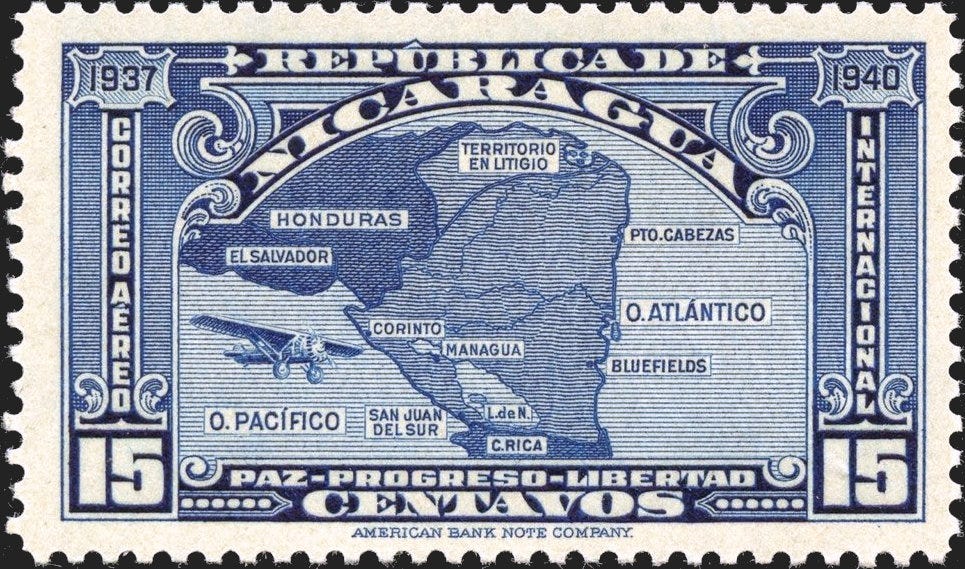

This set, Scott Nr C186-C192, comprised 7 stamps, all with the same design, a monoplane over a map of Nicaragua, with portions of El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Honduras included.

In the north, there is a territory ostensibly belonging to Nicaragua (according to the shading on the map) but labeled, Territorio En Litigio, or Disputed Territory. To understand the dispute, we have to go back over 100 years, to 1820, when the Spanish Empire included most of what is today’s Central America, including Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Costa Rica (and the Mexican State of Chiapas), lacking possesion of only Belize, a British Colony, and Panama which was part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, which eventually became Colombia. These Spanish territories together comprised the five provinces of the Captaincy General of Central America.

So, with that stage set, here are, briefly, the events that led up to the 1937 Nicaragua stamp set:

· In 1821, the Captaincy General of Guatemala declared (and received) independence from Spain.

· The First Mexican Empire (also newly independent from Spain) annexed all of the former Central American provinces (with varying degrees of cooperation from them).

· When the First Mexican Empire collapsed, in 1823, the five Central American Provinces formed the “United Provinces of Central America.”

· Between the years of 1838 and 1840, this federation, too, fell apart, leading to the five provinces becoming independent republics.

· Each new republic adopted the legal doctrine of uti possidetis juris, which states that newly independent states inherit the boundaries which were in place during their colonial administration.

It is at this point where the dispute over the boundaries of the “disputed terrtory” raisses its head. The eastern part of the border between Honduras and Nicaragua was never clearly defined, especially along the Mosquito Coast, due to dense jungle, numerous rivers, imprecise surveys, vague historical demarcations, and issues involving indigenous populations. But as long as the provinces of Honduras and Nicaragua were part of the same kingdom, it didn’t really much matter. Now, though, that they were independent countries, it mattered. Disputes arose between the two countries which failed to get resolved until . . .

The Gámez-Bonilla Treaty of 1894

After a number of persistent border incidents, Honduras and Nicaragua came to recognize the need for a formal approach to settling their dispute. César Bonilla, Secretary of State for Honduras and Dr. José Dolores Gámez Guzmán of Nicaragua, were tasked with representing their respective country’s interests in negotiations. The key provisions of the treaty were –

· The establishment of a commission, with an equal number of representatives from each country, to physically survey and delineate the entire boundary line.

· The adherence to uti possidetis juris, and

· A provision for international arbitration, in case there were points of dispute which could not be resolved by the commision.

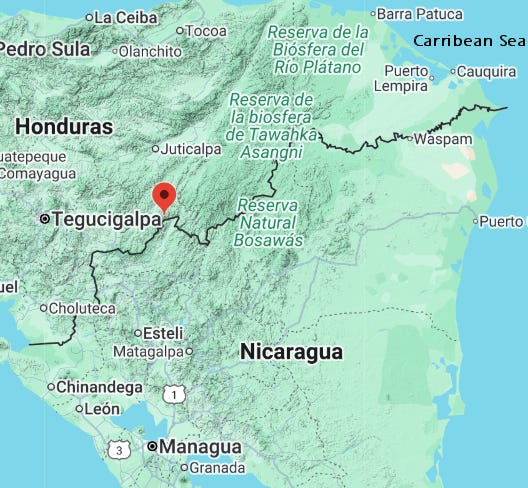

While the drawing up of the western part of the border, from Portillo de Teotecacinte (marked with the red pin on the map above) to the Carribean Sea, was a point of contention between the two parties which proved to be intractable. The decision would have to go to arbitration.

In accordance with the treaty, the boundary dispute was submitted to King Alfonso XIII of Spain for arbitration, a decision amenable to both sides. In 1906, the king ruled in favor of Honduras, a ruling which Nicaragua’s President Zelaya fully accepted . . . at first, going so far as to sending a telegram to the Honduran President, Manuel Bonilla, acknowledging the satisfactory settlement of the boundary dispute by friendly arbitration.

The next year, though, 1907, Zelaya made an about face and demanded clarification of some obscure and contradictory points. For four years his questions remained unresolved and in 1911 Nicaragua’s Foreign Minister declared the arbitration award null and void, citing alleged procedural irregularities and an overstepping of powers by the arbitrator. Honduras insisted that the arbitration ruling was fair and legal and refused to relitigate the matter. For 3 decades, the feud simmered, finally coming to a boil in 1937, with Nicaragua’s issuance of the stamps showing an alleged disputed territory.

Honduras reacted with outrage. They viewed this stamp as a blatant and hostile attempt by Nicaragua to resurrect a claim that Honduras considered settled by the 1906 king's arbitration award. The arrival of mail bearing these offending stamps in the Honduran capital of Tegucigalpa reportedly sparked riots, and Honduran police had to prevent an angry mob from storming the Nicaraguan Embassy. Both countries began sending troops to the disputed border region, bringing them to the brink of armed conflict. Three members of the Organization of American States—USA, Mexico, and Costa Rica—stepped in to mediate. This mediation led to a de-escaltion of tensions and defused the immediate threat of war; however, it did not resolve the underlying dispute.

The dispute continued to fester for another 13 years until, in 1957 both countries agreed to submit their dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), at The Hague, Netherlands. After meticulously reviewing all of the pertinent documents since the beginnings of the dispute, on November 18, 1960, the ICJ delivered a decisive judgment in favor of Honduras, affirming that the arbitration award made by King Alfonso XIII, in 1906, was, indeed, valid and binding. Nicaragua had freely participated in the arbitration proceedings and had, likewise, freely accepted the designation of the king as arbitrator, thus obliging Nicaragua to abide by the decision.

Following the ICJ judgment, a new commision was formed to carry out the surveying and the demarcation of the border in accordance with the 1906 arbitration award. Boundary markers were placed and the land border was finally settled.

The Honduras-Nicaragua border dispute spanned 140 years. The 1937 incident illustrates how even seemingly innocuous national symbols such as postage stamps can carry immense political weight. The issuance of this set of stamps is not the only time that national boundaries came under dispute. In future posts I will cover other similar incidents.

Thank you for reading, and until next time . . .

Happy Stamping

How intriguing. It just so happens I collect Nicaraguan stamps and will be searching for this one.

An interesting post. I have just finished reading a book about a proposed Atlantic-Pacific canal in Central America 100 years before the Panama canal was completed. Also a time of flux in the region with regard to borders, governments and sovereignty.